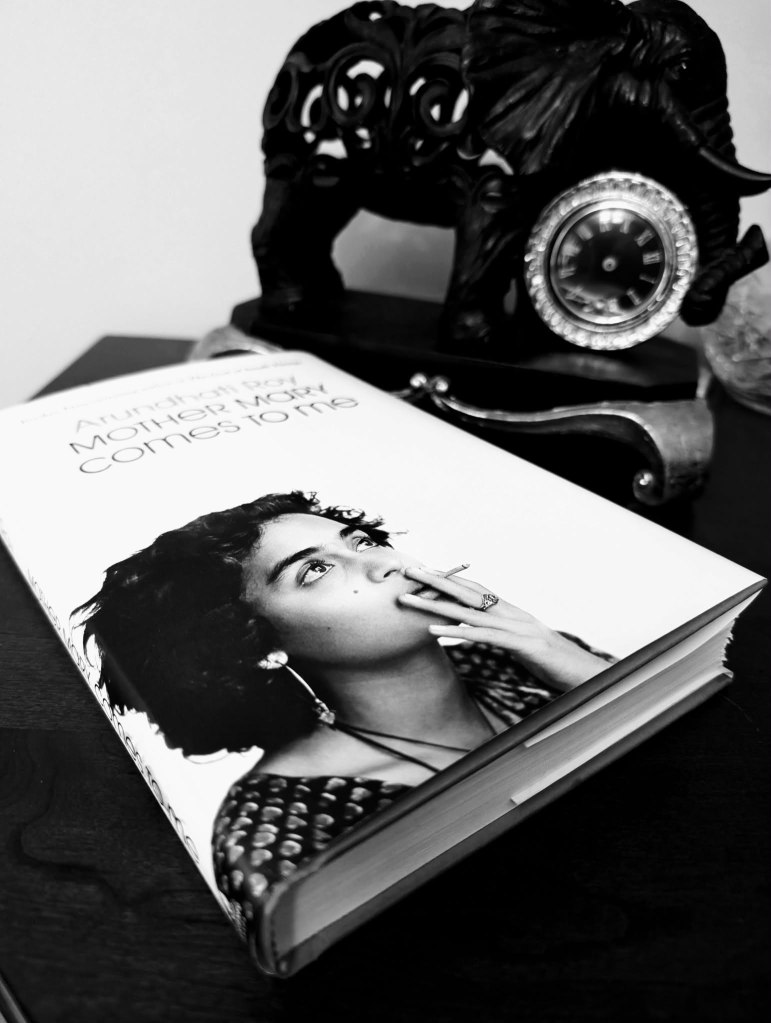

Killing the Mother: Arundhati Roy’s ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me’

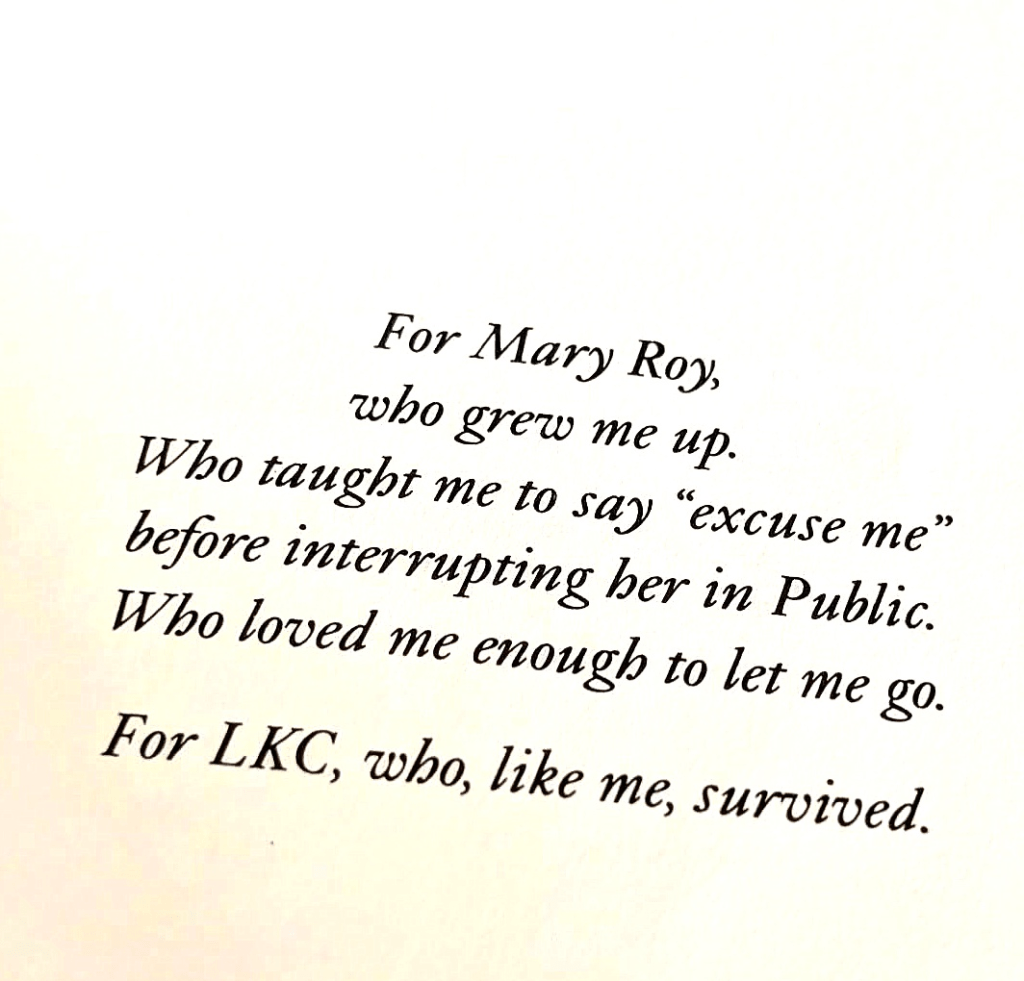

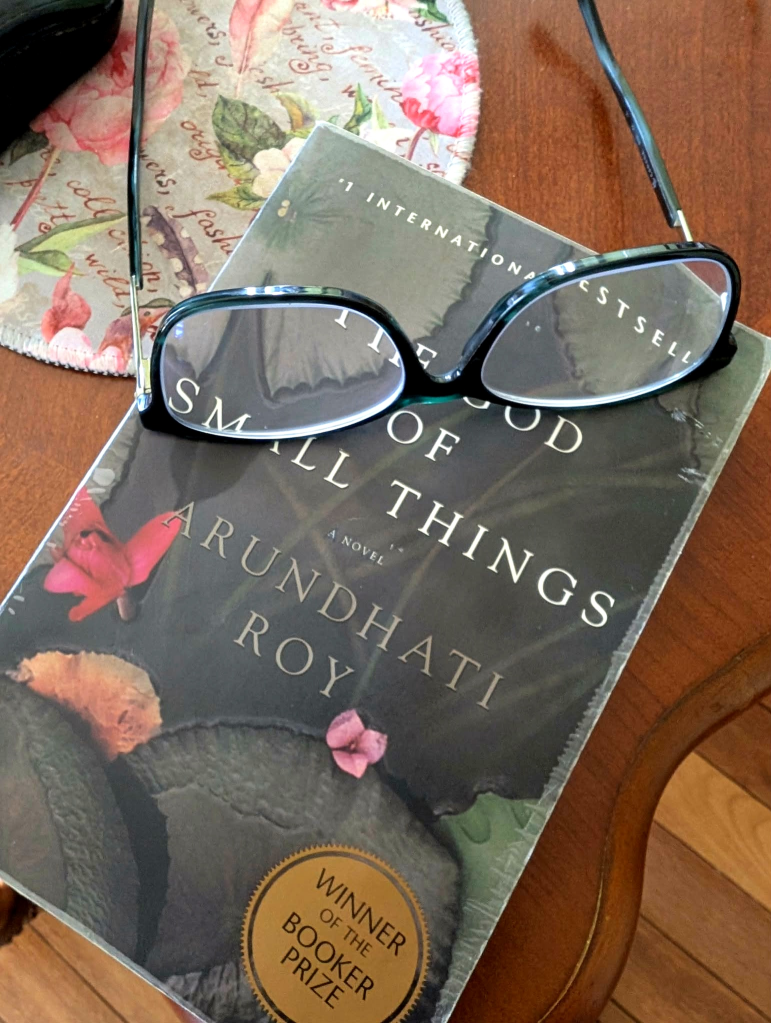

This was in 1998 when the western media was mooning over a novel that had won the Booker, the first time, from the Indian subcontinent. I was in the middle of completing my thesis and the fact that New York Times was lauding it as a novel about the “decline and fall of an Indianfamily” made me think that this could be what I needed to explore. I was into Indo English nation-narratives the post eighties and the nineties. When I turned the first page, what grabbed my attention was the dedication page in which the first mention was one Mary Roy, who “loved her (the author) enough to set her free”. The dedication stayed with me, although I am not quite a quotable quotes junkie. When Mother Mary Comes to Me was announced, I prebooked a copy. The fact that “Ammu” of The God of Small Things was modelled on her was not enough. I needed to know more.

Mother Mary Comes to Me is disquieting. Roy’s memoir makes tantalizing gestures at fictionality, so that at times, it is difficult for the reader to extricate the fictional from the nonfictional in a book that narrates a bruised, humiliated daughter’s love and unlove for a mother whose death she mourns, “a little ashamed by the intensity of [her] response”. Somewhere in the middle, Roy’s memoir of love and loss moves away from her mother, only to arise from the ashes of her pain. As I read on, what struck me was the gradual diminution of Mary Roy, always “Mrs. Roy” for her daughter, to a point when she becomes occasional anecdote. As I read on, I realised the structural gesture was symbolical. Roy asks herself,” “Do we have to kill our own mothers to exorcise this horror that lives inside of us?” when her crazy mother was gone. But the struggle to “kill” Mother Mary does not quite happen. The title of the book is proleptic. Mother Mary returns. Her phantom haunts the narrative and is summed up in a quiet confession: “She loved herself. Everything about herself. I loved that about her.”

Now, what riles me. For Roy, personal has always been political in life and fiction. This is no different. Starting in the sixties, Mother Mary Comes to Me replicates the political idiom of her first novel. This time, her passive radicalism goes beyond Kerala to the Indian state, spanning from the sixties to our turbulent times. Detached, stultifying. It jars; it diminishes; it often displays a style that the author confesses to being poised “between the principled and the hypocritical”. In her interview to Frontline after the publication of The God of Small Things, Roy had commented: “The metaphor [The Heart of Darkness] appears in The God of Small Things as a reversal of Conrad,a kind of laughing reference to‘Heart of Darkness’. It’s saying that we, the characters in the book, are not the White Men, the people who fear the Heart of Darkness. We are the people who live in it […] I keep referring to the war in Vietnam, saying we are the nameless geeks and gooks who populate the Heart of Darkness.” And the project continues.

I am ambivalent about this book.The conflicting narratives in her memoir are often distracting. Let that be. This is not the moment for a searing attack on the politics of language.

I will remember Mother Mary Comes to Me as a threnody by a writer “who has lost her most enthralling subject.”

A must, must read.